Hermann Hartog is released from Sachsenhausen

It was a brutal regime in the concentration camp at Sachsenhausen in November/December 1938. The young rabbi (Leo Trepp) from Oldenburg, who was incarcerated there at the same time as Hermann, remembers all the prisoners being called for a roll-call at 4.00am on a bitterly cold December morning, being threatened by guards with machine guns, and being told,

'You are the dregs of humanity! I don't see why you should live!'

Prisoners such as Leo Trepp and Hermann Hartog had been taken to Sachsenhausen on the morning after the November pogrom. More than 6,000 Jewish men in the larger Frisian area had been rounded up in their various towns and villages, taken by special train to Sachsenhausen, near Berlin (almost 500 kilometres from Wilhelmshaven, where Hermann lived), and imprisoned under a regime where whips and dogs were used by their tormentors to control and terrify them. Some men died as a result of their experiences, including Joseph Haas, who had been a tobacco dealer in Jever and who would have been known to Hermann. No man was left unaffected. This was the point: the prisoners should have no misunderstanding about the intentions of their Nazi rulers. And none of them knew when – or if at all – they would be released.

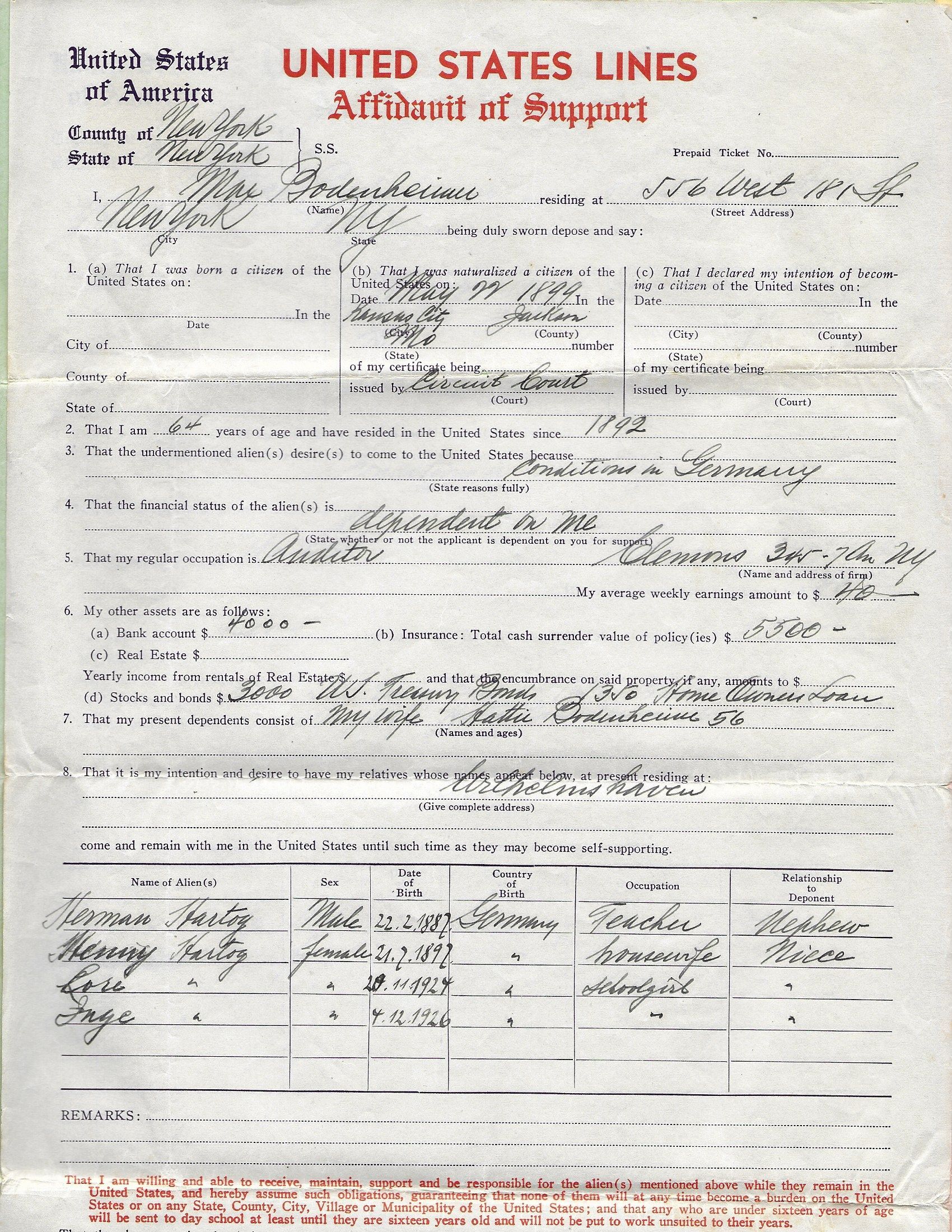

For Hermann Hartog, release came on Monday 12 December 1938 – although he did not know this until the day itself. He had been a prisoner there for over four weeks – and survived. He was allowed to leave because he was over 50; he was, in fact, 51 years old. Part of the formalities for leaving required him to sign a document stating that he would emigrate from Germany, that he was in good health, and that he would not speak of anything that he had seen, heard, or experienced during his imprisonment.

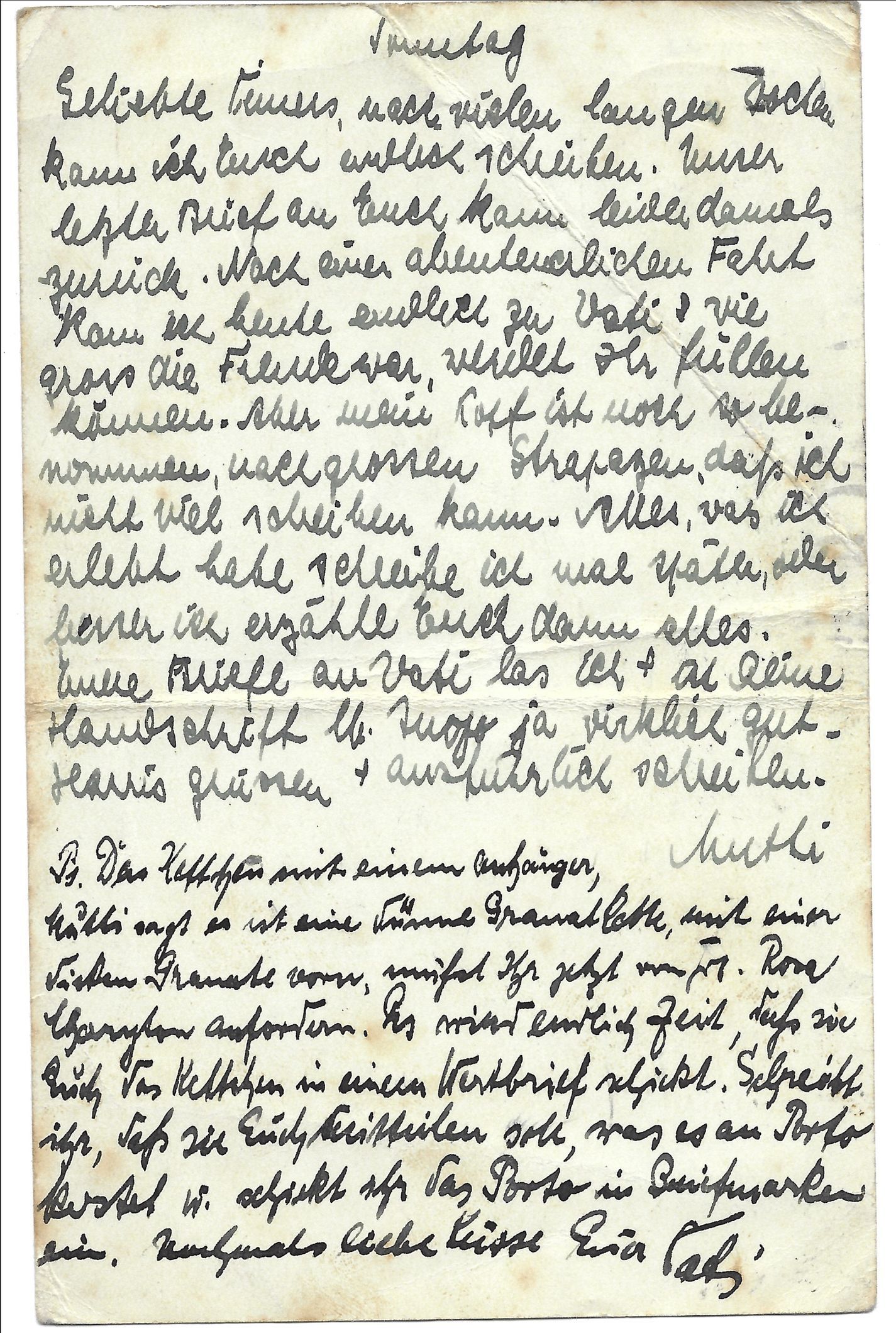

When he arrived back in Wilhelmshaven, he was required to report to the local police station, where he also had to hand over his release papers from Sachsenhausen (according to his later account to the Belgian authorities when he eventually manage to leave Germany). A few days later, the tattered remnants of the Jewish community in Wilhelmshaven attempted to celebrate Hanukkah, the Festival of Lights.

Hermann was not allowed to return to his home at Bismarckstraße 107 as this property was not owned by a Jew. Instead, he and Henny were required to go to a 'Jew House' at Tonndeichstraße 4 - the home of Samuel Mordechai Reisner who had once owned the pawnbroker business that was ransacked and destroyed during the November pogrom.

So much of what had once identified Hermann as a person had been debased and destroyed. He was now obliged to leave his country, and leave behind not only his wider family but also the Jewish community that he had served since his youth. It was a very painful time with agonising decisions to be made.

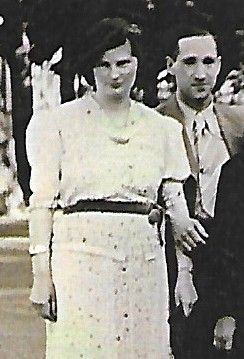

(the photo shows Hermann Hartog in April 1938, before he was imprisoned in Sachsenhausen.)