Evacuation of Dunkirk 1940

'Operation Dynamo', 'The Dunkirk evacuation', or simply 'Dunkirk' took place between 26 May and 4 June 1940. It was the rescue of more than 338,000 Allied soldiers who needed to retreat from the beaches of Dunkirk in northern France as the German army advanced rapidly, surrounded them, and cut them off from further military activity.

During that period, a fleet of more than 800 vessels was hastily assembled to rescue the soldiers. Small vessels with a shallow draught were particularly required to take the men standing shoulder-high in water from the beaches. Pleasure boats, launches, and private yachts set off from the banks of the River Thames and from moorings on the south and east coasts for Ramsgate. There, they had to be verified seaworthy before making the crossing over the English Channel to Dunkirk. The smallest of them was a fishing boat called 'Tamzine', which is now displayed in the Imperial War Museum in London.

As Britain's Prime Minister, Winston Churchill recognised,

'Wars are not won by evacuations'.

Dunkirk was, as he said, 'a colossal military disaster' in which 68,000 soldiers died and in which tanks, vehicles and equipment were lost.

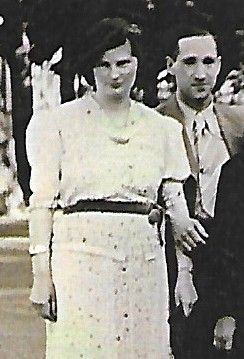

Meanwhile, during those days of chaos on the beaches of northern France, there were other chaotic scenes and disasters elsewhere as people streamed across the French countryside to escape the invading army. Henny and Hermann Hartog were amongst those travelling under arrest from Brussels to Paris, to internment, and to continuing lives as Jewish refugees from the threat of Nazism and from their own native country of Germany. In separate camps in Paris, they had no idea where the other was, and Henny feared for her safety every time a German plane flew over the glass dome of her place of internment. Yet another 'Kristallnacht' seemed imminent. Her young daughters were in England, she was herself in a foreign country, and she was apart from her husband for an unknown time.

Herbert Sulzbach and his wife, Beate, also experienced internment during this time – by the British government. Even though they were Jews who had escaped from Germany, they were seen as a possible threat and interned in separate camps on the Isle of Man. As he was marched between the fixed bayonets of soldiers in Liverpool, Sulzbach was immensely saddened as the civilian population turned away from them – from Jewish people who had tried to escape Nazism and who were themselves fighting against it.

Chaos, confusion, disaster. This had become the norm for ordinary people whether they were serving soldiers, citizens in a new country, or refugees trying to escape an evil regime.

Writing to his non-Jewish friends in Switzerland after the end of this war, Sulzbach wrote,

'My diary of this period is dramatic. After Dunkirk, we conquered only with spirit and the conviction that justice was on our side.'

(photo shows 'Tamzine' in the Imperial War Museum. Photo: Jonathan Cardy 20.12.2016)