Blog

The theme for Holocaust Memorial Day 2026 is 'Bridging Generations'. The Holocaust was, or may seem to be, a long time ago and there are few survivors nowadays to tell us of their experiences of that time. If we cannot bridge the generations, and inspire younger people to remember and care about that event in 'history', maybe the memory will be lost for ever. Does that matter? When a person loses their memory, they are no longer the same person. Similarly, a nation that forgets is in danger of losing its identity. Whatever nation we belong to, we must remember the events of the Holocaust, record them, acknowledge the violence, abuse, and terror that was inflicted on ordinary people - so that we can do all in our power to prevent such atrocities ever happening again. And we must do this even while we know that in some parts of the world similar atrocities are currently already a reality. The accounts of survivors, the testimonies of those who witnessed events, and the documents from those who did not survive may be unfinished or fragmentary, but together they build a monument to the memory of people caught up in one of the worst catastrophies that the world had hitherto known. Creating an active collective memory requires younger people to be part of the memory-making. The need for relevant information and ways of transmitting it to new generations, the participation of young people in establishing a bank of memory against a loss of identity, and their involvement in civic life remains crucial if a nation does not lose its memory and run the risk of repeating horrors from the past. In Wilhelmshaven in Germany, young people have spearheaded a campaign to remember former members of the Jewish community in their city. Almost a year ago, in February 2025, they successfully had laid in their city 'Stolpersteine' [lit: 'stumbling stones'] in memory of members of five families of the former Jewish community that had been deliberately destroyed by the National Socialist Government in the 1930s and early 1940s. As I write, a new cohort of students is researching, recording, and remembering other families so that those people and their contribution to Wilhelmshaven's civic, cultural, and commercial life is rightly appreciated. Young people such as these who keep alive memories and who are active in their communities will, hopefully, be better equipped and able to act against any rise in right-wing radicalism and protect their country's democracy. photo: Wilhelmshaven students, their teachers, the artist Gunter Demnig, and representatives of the former Jewish community after the laying of the last Stolperstein, Thursday 6 February 2025.

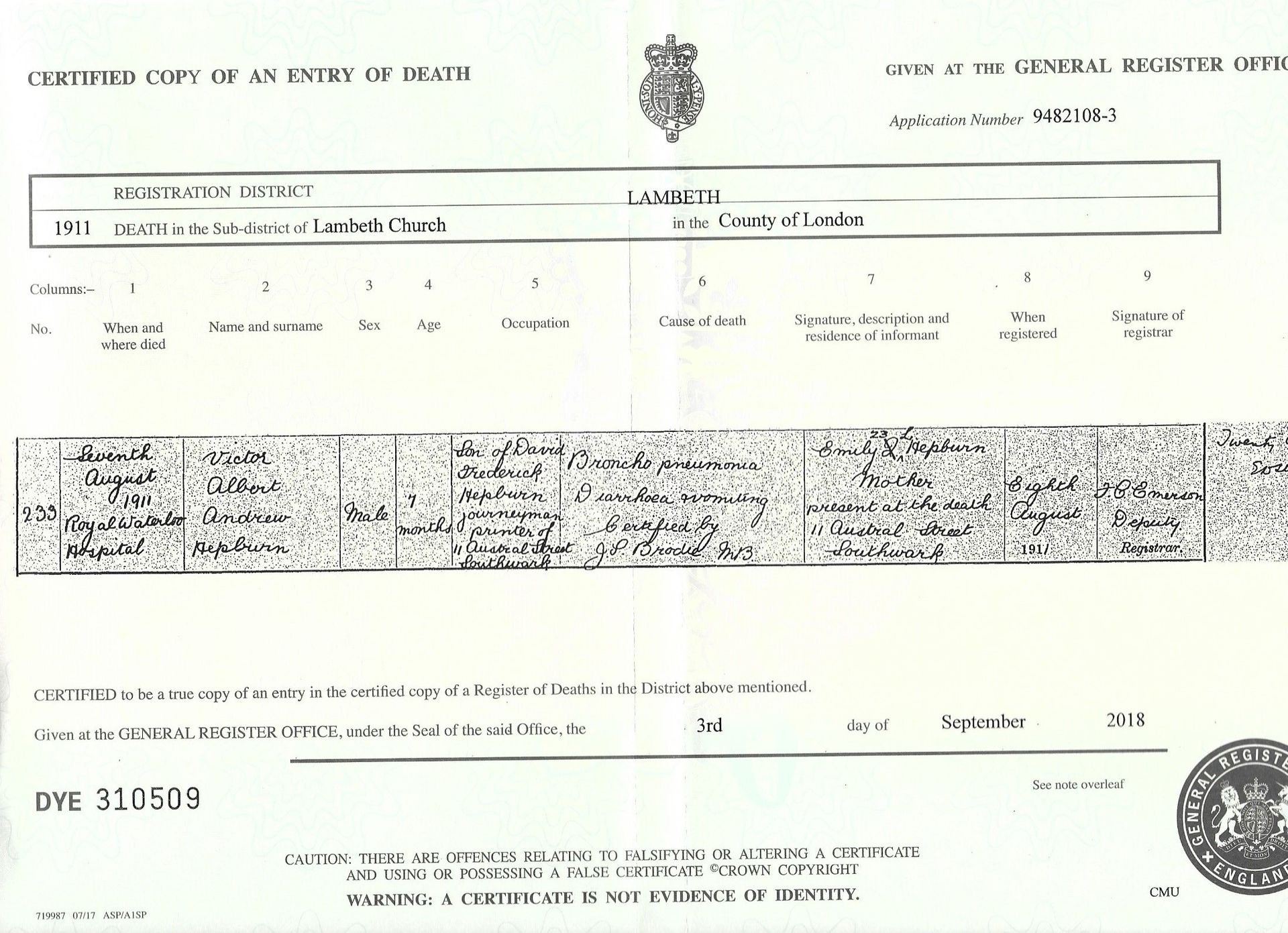

Victor Albert Andrew was the cherished son of Emily and Fred Hepburn. After four daughters, they at last had a son and they honoured him with names from the recent royal family – Victoria and Albert. He was born in January 1911, two years after his sister, Doris, and was baptised in the local church of St Philip in Kennington Road in south London on 7 May. But on 7 August 1911, when he was 7 months old, he died of broncho-pneumonia, diarrhoea and vomiting in the Royal Waterloo Hospital, just one mile from home. Emily was with him when he died. He was by no means the only baby to die during that 'perfect summer' of 1911. It was one of the hottest on record throughout western Europe, and the driest for over a hundred years, with the warmest periods being in early June, and late July to mid-August. From 17 July, temperatures soared and stayed high throughout July and August. There was less than 70% of the average rainfall, with the severest drought coinciding with the time of greatest heat, and with only very light and occasional wind. Victor Albert Andrew died on one of the hottest days of the summer, when the temperature reached nearly 100ºF (37.8ºC). And the weather had alternated between extreme heat and severe cold. On 27 July giant hailstones had fallen on London and brought traffic to a standstill. 'The Times' began a regular column on 'Deaths from Heat' – and the increase in numbers was largely accounted for by infant deaths. In poorer communities, intestinal infectious diseases were difficult to control and were often fatal for very young children, especially if they lived in crowded accommodation. No-one had refrigeration or air conditioning and babies died from diarrhoea associated with rotted food and bad milk. This massive and sudden jump in the medical health statistics was particularly high in this area of south London. The noxious smells in the streets intensified, no rain fell, and many people planned to escape the town during the Bank Holiday. Emily Hepburn did not go to the seaside. It was Bank Holiday Monday when her baby son died. It must have been a terrible, long and weary walk back home from the hospital - through the hot and smelly streets – almost a mile down the Waterloo Road, and then a few streets further on past the Bethlem Hospital before she was home in Austral Street. Once there, she had the care of her other young children. Emily Mary, the eldest, was just eight years old, Ruby Grace was six, Rosina May four, and Doris Winifred was still only two. Many years later, it was still told in the family how keenly Emily felt the death of her little son, and how much she grieved for him. ( photo shows the death certificate of Victor Albert Andrew Hepburn)

Thirty years after the Second World War, the cousin of Amélie Derrez, François Casabonne, described her as a member of the Resistance. She lived in the village of Arette in the south-west of France, near to the Spanish border, was married to the secretary of the mayor, and perhaps does not fit the popular idea of a Resistance fighter. She did not carry arms – as far as I know – and in the early years of the war, when Arette was not occupied by German forces, she certainly did not belong to a recognised group of people intent on subversive activity. Rather, her sense of propriety, her devout Catholic beliefs, and her ingrained Basque traditions made it impossible for her to treat other people as the Nazis expected. While her resistance was passive, it was powerful. Amélie was married to Gaston Derrez who worked in the town hall in Arette as secretary to the mayor. He was known in the village at that time as someone who was prepared, for example, to make sure that documents were available for young men who wished to leave to escape official transfer to Germany as slave labour. The escape routes across the nearby mountains of the Pyrénées were managed by local shepherds and available for fit young men who wished to join the Free French in Algeria – and who had the necessary paperwork. The mayor at the time was Pierre Casabonne – a relative of his wife's family – who belonged to a respected local family that was devoutly Catholic. During the Second World War, many people in France supported the persecution of Jews, communists, and foreigners. At the beginning of the war, the people of the Basque areas generally supported the Vichy regime which was sympathetic towards traditional regions. Amélie Derrez resisted. She demonstrated her resistance by helping the Jewish refugees who had arrived in her village at the beginning of 1941. There were many refugees in the village, but only a few foreign Jews amongst them. Amélie befriended the women – Henny Hartog, Elisabeth Preis, and Elisabeth's mother, Gertrud Schück – and invited them to her house. Every afternoon, they gathered around her kitchen table to talk, share experiences, advise each other – and listen to the radio (itself a subversive act). They listened to 'Radio Londres' – the BBC broadcasts in French to France – and so had more up to date, reliable news than anyone else. There were very few radios in the village, but these women were able to stay informed about the progress of the war, know that they were ahead of the rumours, and keep sane as their world shifted around them. They also created bonds of friendship. When Henny worried about her husband being drafted into a work camp for foreign men, Amélie found work for him in the village with her cousin. When Henny was deported from Arette, she wrote a final, heart-broken letter to Amélie, and Amélie grieved the sudden departure of her Jewish friends for many years. In 1947, she was still in correspondence with another refugee to ask what she should do with items that had been left with her for safe keeping when people had been taken away from the village. Amélie Derrez died in Arette on 14 June 1950, aged 60. Her husband, Gaston Derrez, died there on 8 December 1958, aged 74. (photo of Amélie Derrez)

The camp at Gurs in south-west France, about 40 kilometres from Pau, was constructed in 1939 as an internment camp and prisoner of war camp. It was initially set up by the French government to receive those fleeing Spain at the end of the Spanish Civil War. In 1940, when France signed an armistice with Germany, the camp was then used to house foreign Jews and other 'undesirables'. The first contingent arrived on 21 May 1940. A few months later, in October 1940, the Nazis decided to evacuate all the Jews from Baden and send them westwards to Gurs. That month, some 6,500 to 7,500 Jews arrived in Gurs adding significantly to the crisis of accommodation for the refugees in the area. In 1942, most of the Jews in the area were taken to Camp de Gurs as part of the Nazis' Final Solution in exterminating the Jews. Beginning in August 1942, they were then sent from Gurs in convoys to the internment camp at Drancy in Paris from where they were deported to extermination camps 'in the East'. Most of them were murdered in Auschwitz. The camp was dismantled in 1946. More than thirty years later, in 1979, the 40 th anniversary of the creation of the camp, young people in the area started to explore their past and began to invite ex-inmates of the camp to conferences and lectures. This was much-publicised locally and led to an event the following year when there was a reunion at Gurs on 20 – 21 July. The reunion drew people from many countries who had been former detainees, as well as others who had been associated with the French Resistance, or those who had survived the Death Camps. Together, they created an organisation called 'L'Amicale de Gurs' ('Friends of Gurs') which now has its own newsletter and also holds an annual commemorative ceremony that is attended by various Jewish organisations, representatives from Baden, as well as local officials and supporters. The event commemorates the people who have passed through Gurs and suffered there, and it draws attention to the evils of dictatorial political regimes. Remembering the people and the place makes us all aware of the need to keep alive these memories and use them to inspire us to an active commitment to ensure – in whatever way we are each able – that we are involved in creating a society that turns away from intolerance, racism, cruelty and violence and builds something better in its place. (the photo shows part of an earlier year's commemoration)

The Vel d'Hiv (short for Vélodrome d'Hiver) round-up was a mass arrest of Jews in Paris on 16 July 1942 by Vichy police at the request of the German occupying authorities. It was part of a plan to eradicate Jews from all of France. The round-up was part of the 'Final Solution' decided at the Wannsee conference in January 1942, and was a jo int operation between German administrators and French collaborators. The Vel d'Hiv was a large indoor sports stadium with a cycle track and had already been used as an internment location for Jewish women in the summer of 1940, when Henny Hartog had been one of the women interned there. There had been other round-ups in France earlier in the year but they had failed to deliver the numbers of Jews promised to the Germans. This one was aimed at all foreign Jews aged from 16 to 50, although exceptions were made for some women. It was intended that children would be sorted at the assembly centre but many children were eventually included in the final number. The director of the city police ordered that 'the operations must be effected with maximum speed, without pointless speaking, and without comment'. The round-up began at 4.0am on Thursday 16 July 1942 with 9,000 policemen involved. They carried with them detailed lists of the names and addresses of those Jews they were searching for – information that had been carefully collected from existing records and censuses in the city. In total, 13,152 Jews were arrested, including 5,802 women and 4,051 children. They were each allowed to take with them a blanket, a jumper, a pair of shoes and two shirts. Inside the Vel d'Hiv the summer heat was intense. with the effect of the sun through the darkened glass roof increasing the temperature. All windows were blocked, there were no toilets, and the only food available was that being supplied by Quakers and members of the Red Cross. Anyone who tried to escape was shot and there were some who committed suicide. After five days, the detainees were taken to other internment camps in France and from there to Auschwitz and other extermination camps. A fire destroyed part of the Vel d'Hiv in 1959 and the rest of the structure was afterwards demolished. On 3 February 1993, the French President, François Mitterand, commissioned a monument to be erected on the site and this now stands nearby, on the Quai de Grenelle, by the side of the River Seine. It is the work of the Polish sculptor, Walter Spitzer, who was himself a survivor of Auschwitz. The sculpture includes children, a pregnant woman, and a sick man. It was inaugurated on 17 July 1994. (the photo shows the sculpture)

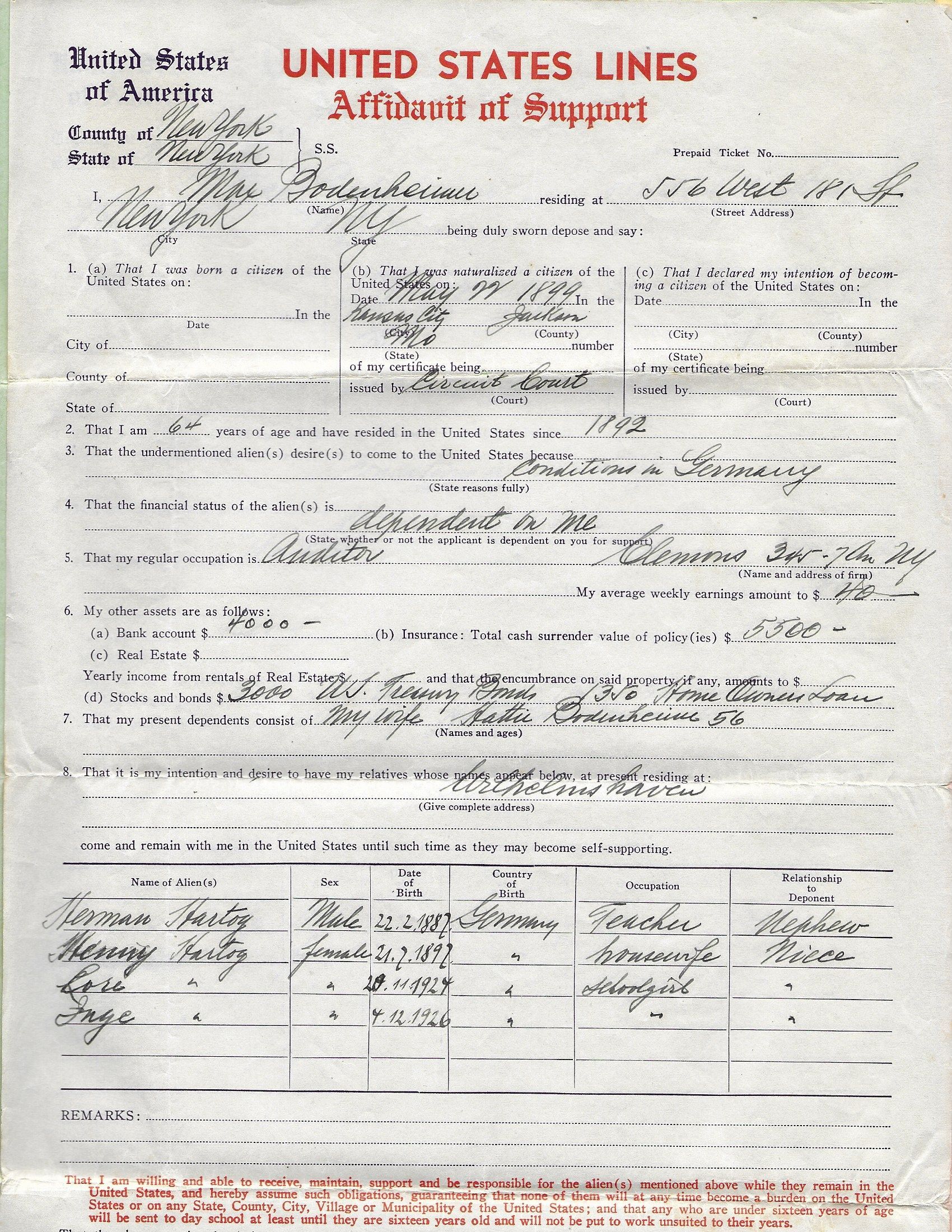

During the 1930s, the USA had no designated refugee policy; it only had an immigration policy. American public opinion did not favour increased immigration as many Americans feared that immigrants would 'steal' their jobs. In order to prove that they would not be an economic burden on the state, prospective immigrants had to find an American sponsor who would guarantee their financial resources in an affidavit. The immigration process was slow, with strict quotas limiting the number of people who could immigrate each year. The immigration laws were never revised or adjusted between 1933 and 1941. As in Europe, there were Americans who believed that the rapid military success of the German army in May 1940 could be attributed to the work of spies, and there was concern that Germany was then taking advantage of the masses of Jews trying to flee by sending spies abroad. So, consular officials were urged to take extra care screening applicants for immigration, and in June 1941 a 'relatives rule' was also issued, denying visas to prospective immigrants who still had family members in Nazi-controlled territories. On 1 July 1941, the American State Department centralised all visa control in Washington DC. A new review was ordered for each applicant and extra documentation was required, including a second financial affidavit. From that date, emigration from Nazi-controlled territory became virtually impossible. As a result, many thousands of Jews who had applied at American consulates in Europe no longer had any chance to immigrate. Many of them were subsequently murdered in the Holocaust by the Nazis. Henny and Hermann Hartog were clearly aware of these developments and the new regulations. During the rest of that summer, they both had to come to terms with the likelihood that their emigration would not happen. They were intensely sad at this turn of events and Hermann wrote about his bitter disappointment that their relatives in America could not manage to raise the (very substantial) sum of money they needed for the fare. To have come so far in the emigration process, and to be denied success because of a lack of resources and an extreme tightening of the regulations over which they had no control, was a very cruel blow. As Hermann wrote to his daughters on 6 July 1941, 'We hear that more specific regulations are again coming from America, so all of our work was probably over and we start again from the beginning. So we have little hope that we can go to America. And whether we survive the war lies in God's hand, because no-one knows how long this war will last, and what will become of us.' (photo shows the original affidavit for the Hartog family)

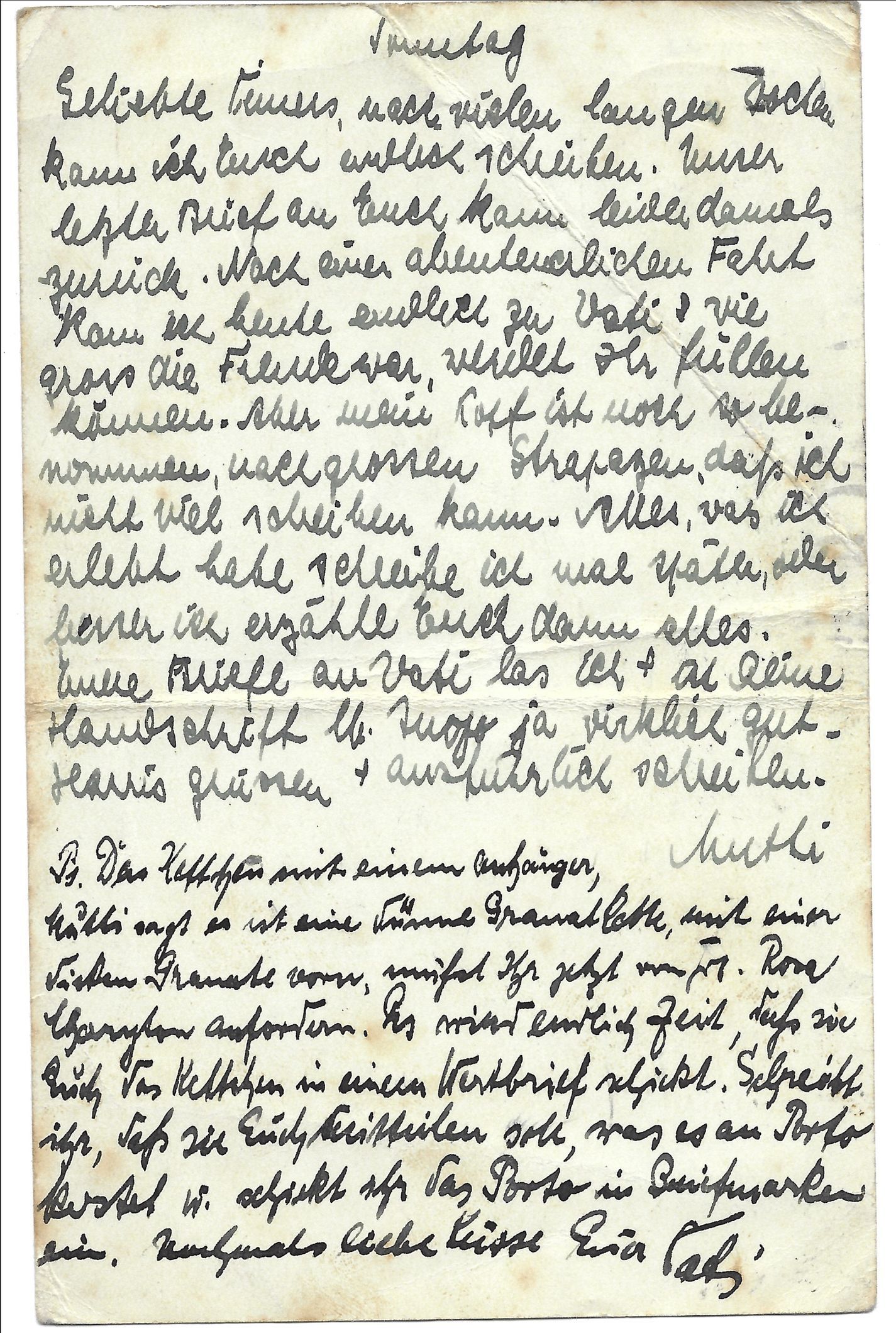

During the Second World War, the main way that people who were separated from each other could connect was through letter-writing. In our own family, letters that we discovered gave us a new understanding of a time and experience that our parents had never wished to discuss. Fragile bits of paper, with almost undecipherable writing in a foreign language, took us on an intense journey of family discovery. My husband's grandparents, Henny and Hermann Hartog, had lived in Germany with their two young daughters. Both of them were from Jewish families and he was a teacher and cantor in the synagogue. During the 1930s, they sent their elder daughter to England for the education that was denied to her in Germany, and their second daughter arrived in England on the first Kindertransport in December 1938. Henny and Hermann fled to Belgium and then lived as refugees in France before they were deported. Throughout this time, their only family contact was through letters. At first, these letters were frequent and long, with the parents trying to bring up their children from afar, checking out their clothes, their school reports, giving advice about behaviour and education – and confident for a future where they would all soon live together again in America. In May 1939, they even agreed with their children that the girls would write on a Saturday so that this letter was received by their parents on the following Tuesday and an immediate reply could arrive in England by the end of the week, on the Sabbath. This efficient plan could not survive war. When Henny and Hermann became refugees in France, they found themselves anxiously awaiting letters in a deteriorating postal system. France had become an enemy of Britain, so it was difficult to send or receive mail between the two countries. Henny and Hermann continued to write once a month to their daughters and waited anxiously for replies that never came. They suggested new routes for the post. These included writing through a mutual friend – a fellow Jewish teacher, Max Ruda, who lived in Zeurich, in neutral Switzerland. The International Red Cross helped with some postal arrangements, and there were suggestions about sending letters with a reply slip via organisations in Lisbon, but it was a rare occasion when a letter got through – and a time for celebration when a bundle of several very occasionally turned up all at the same time. As Henny wrote, 'It was a great joy and surprise for us when finally a letter from you arrived, and we are even happier that you received the six letters from us! In any case, we have many worries but our greatest joy is when we receive good and frequent letters from you.' In France, people increasingly recognised the presence of police terror, informers and collaborators in their communities. They shared less with each other in their conversations, and letters became comparatively bland. Henny and Hermann no longer mentioned the names of any of the people who were helping them. Everyone was beginning to wall themselves into a silence that they hoped would give better security. By 1942, everyone was grateful for any letters because they showed that the people who mattered to them were still alive. These letters came ultimately to tell merely the often trivial details of their daily lives, and remembrances of happy times that they had once spent together. In the end, it mattered only that a letter confirmed that the correspondent was still alive, that they sent a message of reassurance that they still deeply loved the recipient, and the affirmation that they all continued to hope and pray for better times. For Henny and Hermann's daughters, letters from their parents had been arriving increasingly infrequently and always delayed, and then they just never came at all. (photo shows a postcard from Henny and Hermann to their daughters, October 1939)

Two very different Jewish women, who never knew each other but who had both fled Nazism in Germany, found themselves interned in June 1940. Beate Sulzbach was 43 years old and had been living as an emigré in London for just two years when she was arrested and interned – first in Holloway Prison and then on the Isle of Man. She married Herbert Sulzbach in 1923 and during the 1920s she enjoyed her professional life as an actress in the Expressionist theatres in Berlin. She had no children. Henny Hartog was 42 years old and had been living as an emigré in Brussels for only seven months when she was arrested and interned – first in Paris and then at Camp de Gurs in south-west France. She married Hermann Hartog in 1921 and was his support and home-maker while he worked as a Jewish teacher and cantor in synagogues in north-west Germany. They had two young daughters who had been sent to safety in England. For both women, the rapid advance of the German army in May 1940, followed by the fall of Belgium, the Netherlands and then France brought confusion, alienation, and threat to their lives. There were people throughout western Europe who believed that the speed of the attack had only been possible because of insider help. A very public outcry was raised that there must be spies everywhere. Suspicion was directed first at any people of German origin. It was seen as irrelevant that those same people had themselves fled the regime in Germany, and had been either targets of that regime or fighting against it. Fear and distrust were intensified by the actions of national newspapers that whipped up hatred and xenophobia amongst their readers. For both Beate in London, and for Henny in France, this was a frightening, bewildering, and extremely upsetting time. Their husbands were interned at the same time as them – but in separate places. Neither of them knew their whereabouts for several weeks. Beate stayed in Holloway prison for four weeks before being transferred to Port St Mary on the Isle of Man. There, she was under house arrest in a large boarding house with several other women, required to share this space (and also her bed) with a complete stranger. She was released eight months after her initial arrest. She tried to find beauty and positivity in her experience and wrote to her husband, 'We can walk, and walk without seeing any barbed wire. My boarding house is by the beach. I am sitting in the window and looking over the sea and the sun is shining.' Henny stayed in Camp de Gurs for over four weeks until her husband found her after his own release. They were then both given refuge in a nearby village where they lived under house arrest for the next two years until they were deported to Auschwitz. Henny tried to stay strong and positive throughout her experience, writing to her daughters, 'Now we are in a little village in the mountains near the Spanish border. We are together with other refugees and we are in good health.' Beate survived internment and the war largely because she had found refuge with the victorious nation. Henny was murdered in September 1942 because the French government collaborated with their German occupiers to deliver the required quota of Jewish people to the extermination camps and she was included in that number. Both were victims of the racism, intolerance, and cruelty of those times. (photo shows the boarding house where Beate was interned on the Isle of Man)

In May 1940, Germany combined attacks with tanks, infantry and artillery to overwhelm the defences of Belgium and Holland before deploying the same tactics against France. German forces invaded France through the rugged terrain and dense forests of the Ardennes – an area thought to be impenetrable by French and British generals. The Maginot Line defences built in France were totally ineffective against the rapid German onslaught. On 9 June 1940, the French government fled from Paris and moved to Tours. The German forces advanced towards the northern French coast, forcing the British forces to retreat from Dunkirk. They also quickly turned towards Paris and entered the city on 14 June. French forces and many of the citizens of Paris had already left and the German soldiers entered a silent place. Two million Parisians had departed and all the shops and businesses were closed. Paris was formally declared an 'open city', meaning that it would not be defended so that its destruction could be prevented. Meanwhile, those Parisians who had left their homes, together with people who had fled from northern France, Holland and Belgium ahead of the advancing Germans, escaped southwards for safety. They piled their belongings high into carts, wheelbarrows and prams as they joined the flood of people trying to move along the roads. Those with cars and lorries soon ran out of fuel and abandoned their vehicles to continue on foot with this huge wave of humanity trying to escape the Germans. Meanwhile, those same German invaders strafed the columns of people from planes above them as they made their slow way south. It was chaos. Absolute chaos. People travelling south slept wherever they could – under the hedges alongside the road, in empty barns along the route, in the corners of fields. When the food supplies that they had brought with them ran out, they raided abandoned homes and farms for something to eat. Shopkeepers along the way were often generous with offers of food, but there was not enough for everyone to eat. When war had been declared nine months previously, the French authorities had put in place schemes for a fair distribution of food and a rationing of resources, but the rapid turn of events of June 1940 had not been anticipated and the tidal wave of thousands of refugees from northern France towards the southern towns and villages was far greater than anyone had expected. There was panic, chaos, and confusion everywhere. (photo shows people fleeing Paris in June 1940 © LAPI/Roger Viollet)

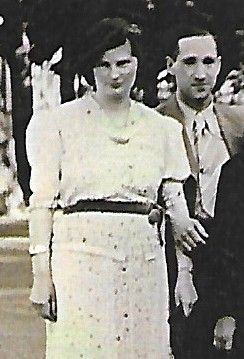

Eighty seven years ago, on 16 June 1938, Arthur Bodenheimer and his new wife, Sitta Siesal, sailed from Hamburg to the United States of America. They arrived eight days later, on 24 June, in New York and went through the usual immigration process at Ellis Island. Arthur was 29 years old and Sitta was 24. They travelled to their new home with Sitta's parents, Moritz and Selma Siesal who were then 55 and 52 years old. Arthur's parents, the slightly older Louis (62 years) and Hedwig (65) remained in Germany where Louis still had a business in the selling of second-hand clothing. Louis Bodenheimer had already sold part of his business to finance the emigration of his son. Leaving Germany was an expensive undertaking, with taxes and extra payments required at every turn by the Nazi authorities. The Reichsfluchtsteue r (Reich Flight Tax) was a stringent tax to limit the amount of currency and property that Jews could take out of the country with them. When Arthur Bodenheimer emigrated from Frankfurt to America, his father paid 5,000 Marks in Reichsfluchtsteuer . In order to find the money to do this, he had to sell one of his properties. For many people, the tax was such a prohibitive restriction that it actually made emigration impossible. Hermann Hartog knew about Arthur and Sitta's plans to emigrate. In August 1937, he had travelled from Wilhelmshaven to Frankfurt to officiate at their marriage at the Pension Rosiner. Arthur continued to hope that his parents would be able to join them in the USA. In April 1941, he wrote to Henny and Hermann, 'Six weeks ago, I paid for the tickets for the ship for my dear parents, and I still have to pay for their journey from Germany to Lisbon.' Six months later, on 20 October 1941, Arthur Bodenheimer's parents were taken on the first deportation from Frankfurt to Łódź. According to a note in the Reich currency files, Louis' considerable fortune was used 'for the benefit of the Reich'. He was 65 years old and Hedwig was 69. Hedwig died in Łódź seven months later on 17 May 1942. Three months afterwards, in August 1942, Louis died there of a weak heart. Many years later, Henny and Hermann's younger daughter, Inge, won some lottery money and chose to use it to see her relatives in America. She was extremely pleased to meet those few members of her family who had managed to make a new start in America. (the photo shows Arthur and Sitta on their wedding day on 8 August 1937)