Resistance in Arette 1940 - 1945

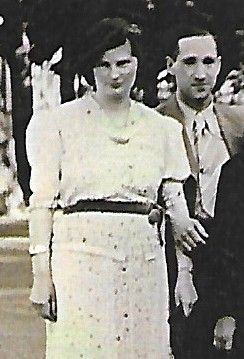

Thirty years after the Second World War, the cousin of Amélie Derrez, François Casabonne, described her as a member of the Resistance. She lived in the village of Arette in the south-west of France, near to the Spanish border, was married to the secretary of the mayor, and perhaps does not fit the popular idea of a Resistance fighter.

She did not carry arms – as far as I know – and in the early years of the war, when Arette was not occupied by German forces, she certainly did not belong to a recognised group of people intent on subversive activity. Rather, her sense of propriety, her devout Catholic beliefs, and her ingrained Basque traditions made it impossible for her to treat other people as the Nazis expected. While her resistance was passive, it was powerful.

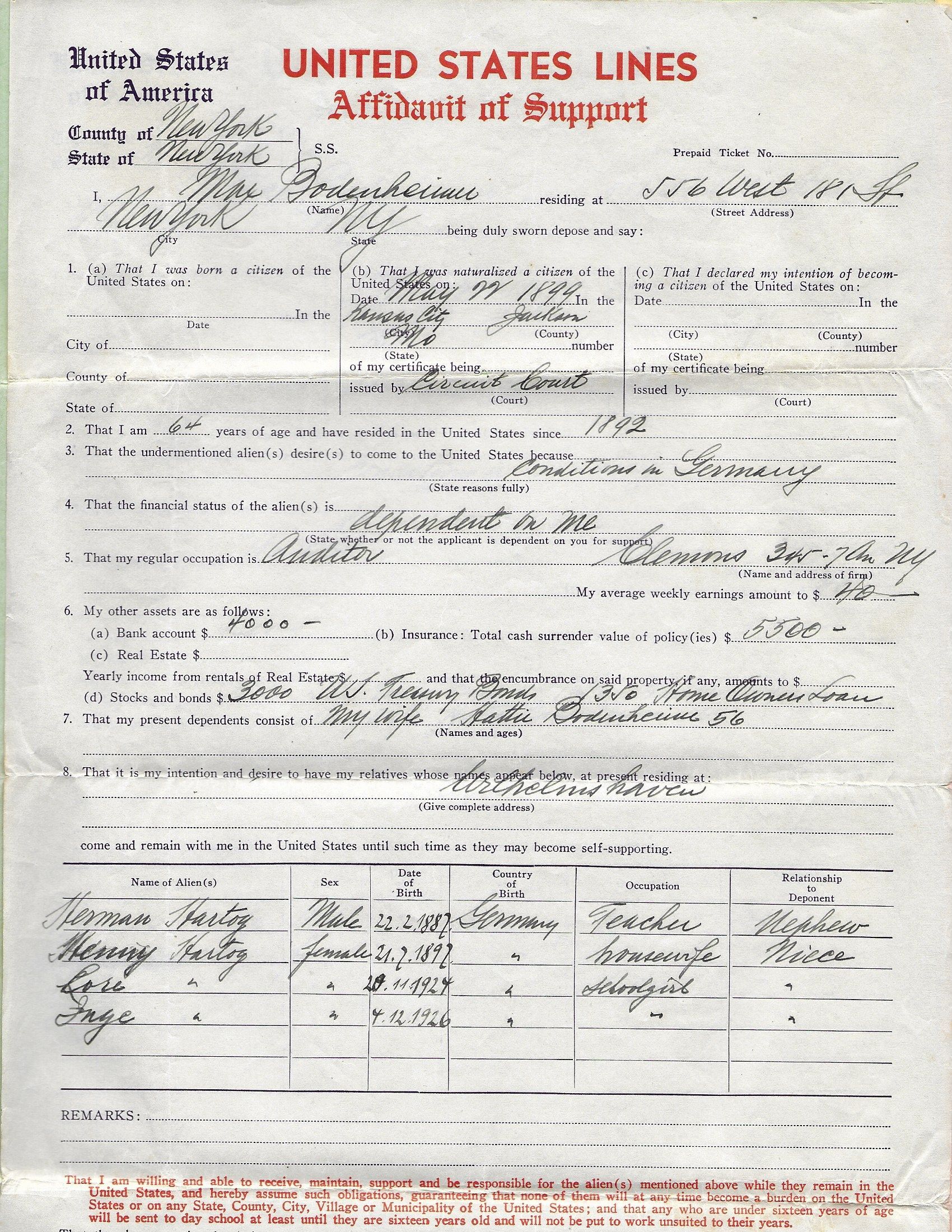

Amélie was married to Gaston Derrez who worked in the town hall in Arette as secretary to the mayor. He was known in the village at that time as someone who was prepared, for example, to make sure that documents were available for young men who wished to leave to escape official transfer to Germany as slave labour. The escape routes across the nearby mountains of the Pyrénées were managed by local shepherds and available for fit young men who wished to join the Free French in Algeria – and who had the necessary paperwork. The mayor at the time was Pierre Casabonne – a relative of his wife's family – who belonged to a respected local family that was devoutly Catholic.

During the Second World War, many people in France supported the persecution of Jews, communists, and foreigners. At the beginning of the war, the people of the Basque areas generally supported the Vichy regime which was sympathetic towards traditional regions. Amélie Derrez resisted. She demonstrated her resistance by helping the Jewish refugees who had arrived in her village at the beginning of 1941. There were many refugees in the village, but only a few foreign Jews amongst them. Amélie befriended the women – Henny Hartog, Elisabeth Preis, and Elisabeth's mother, Gertrud Schück – and invited them to her house. Every afternoon, they gathered around her kitchen table to talk, share experiences, advise each other – and listen to the radio (itself a subversive act).

They listened to 'Radio Londres' – the BBC broadcasts in French to France – and so had more up to date, reliable news than anyone else. There were very few radios in the village, but these women were able to stay informed about the progress of the war, know that they were ahead of the rumours, and keep sane as their world shifted around them.

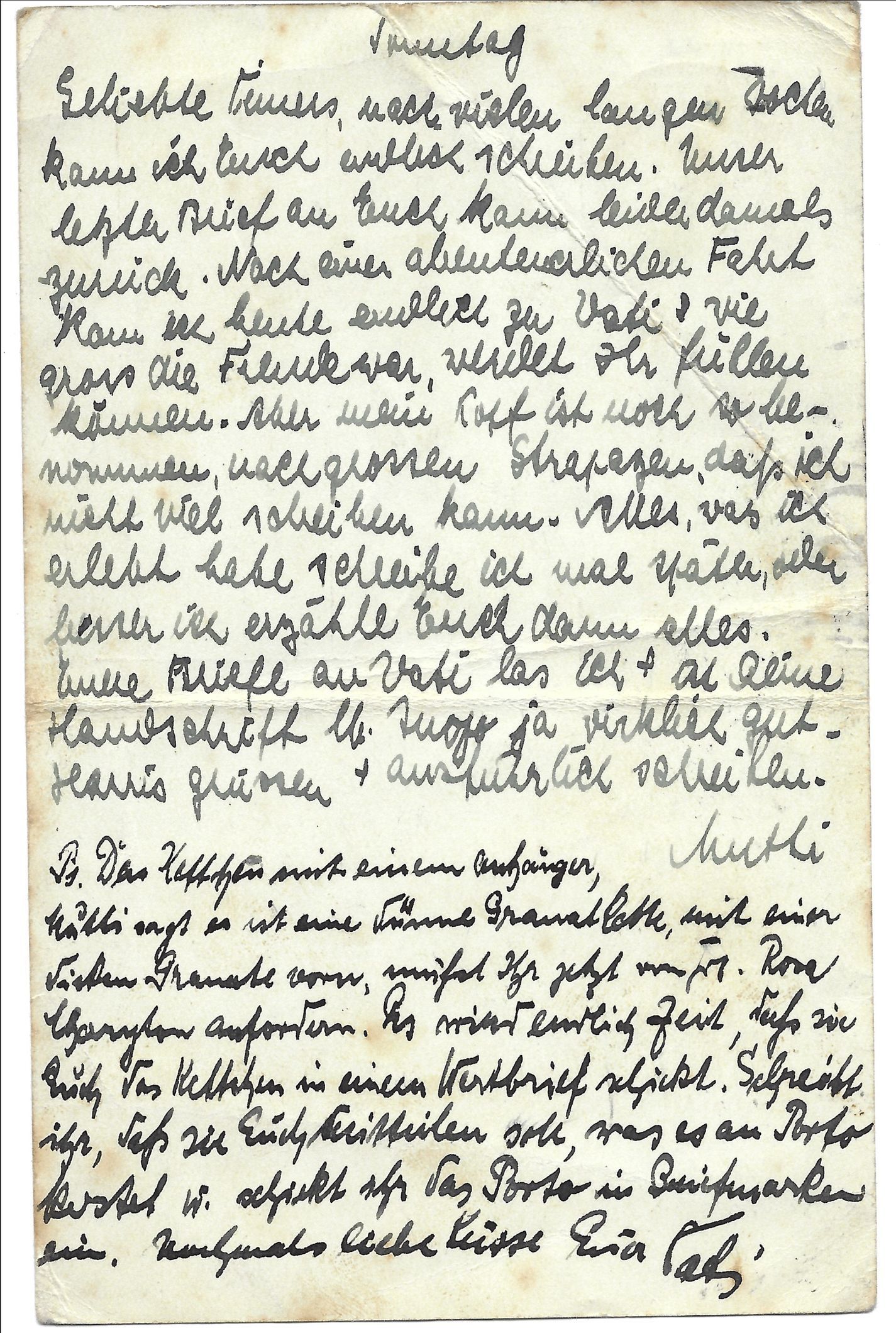

They also created bonds of friendship. When Henny worried about her husband being drafted into a work camp for foreign men, Amélie found work for him in the village with her cousin. When Henny was deported from Arette, she wrote a final, heart-broken letter to Amélie, and Amélie grieved the sudden departure of her Jewish friends for many years. In 1947, she was still in correspondence with another refugee to ask what she should do with items that had been left with her for safe keeping when people had been taken away from the village. Amélie Derrez died in Arette on 14 June 1950, aged 60. Her husband, Gaston Derrez, died there on 8 December 1958, aged 74.

(photo of Amélie Derrez)