When Letters are the only Way to stay Connected

During the Second World War, the main way that people who were separated from each other could connect was through letter-writing. In our own family, letters that we discovered gave us a new understanding of a time and experience that our parents had never wished to discuss. Fragile bits of paper, with almost undecipherable writing in a foreign language, took us on an intense journey of family discovery.

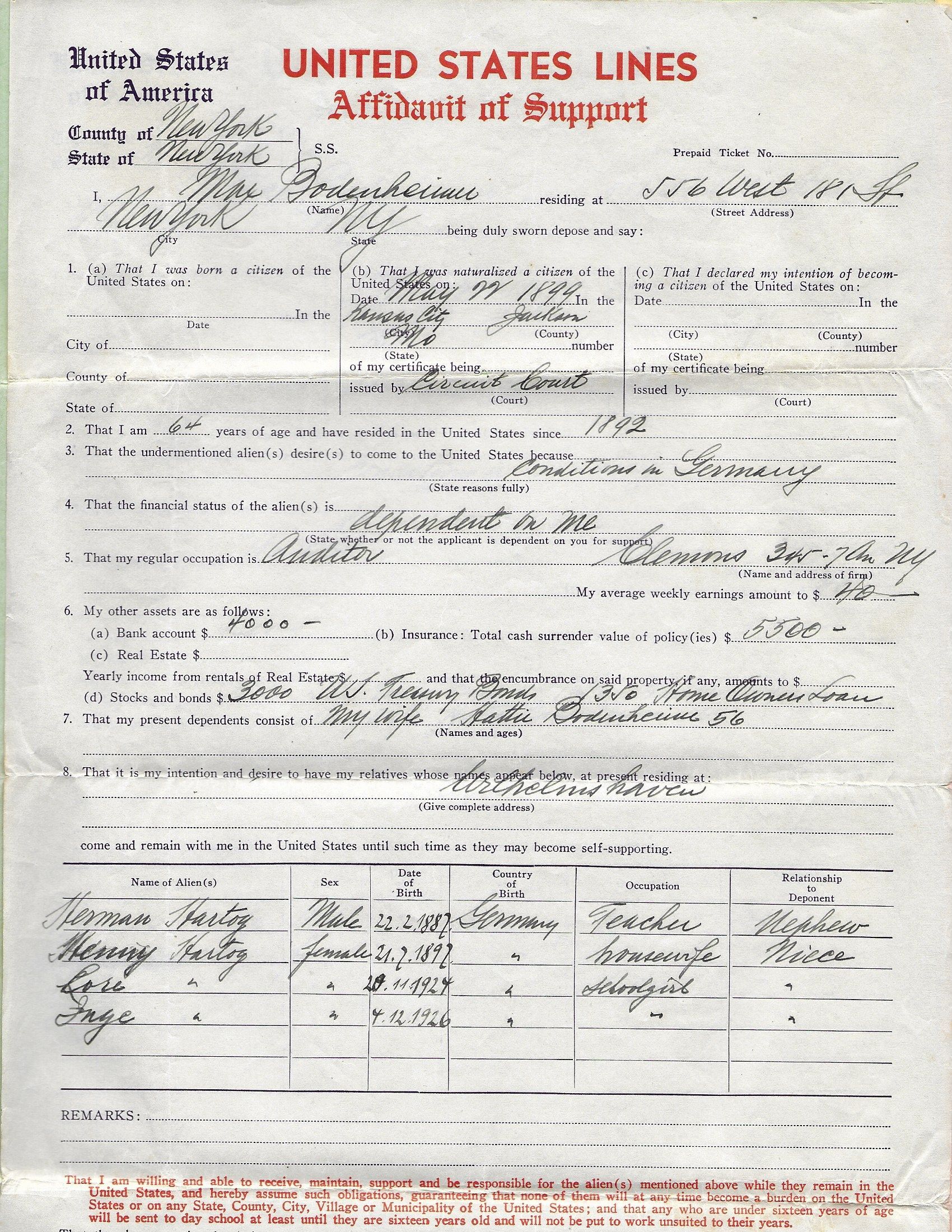

My husband's grandparents, Henny and Hermann Hartog, had lived in Germany with their two young daughters. Both of them were from Jewish families and he was a teacher and cantor in the synagogue. During the 1930s, they sent their elder daughter to England for the education that was denied to her in Germany, and their second daughter arrived in England on the first Kindertransport in December 1938. Henny and Hermann fled to Belgium and then lived as refugees in France before they were deported.

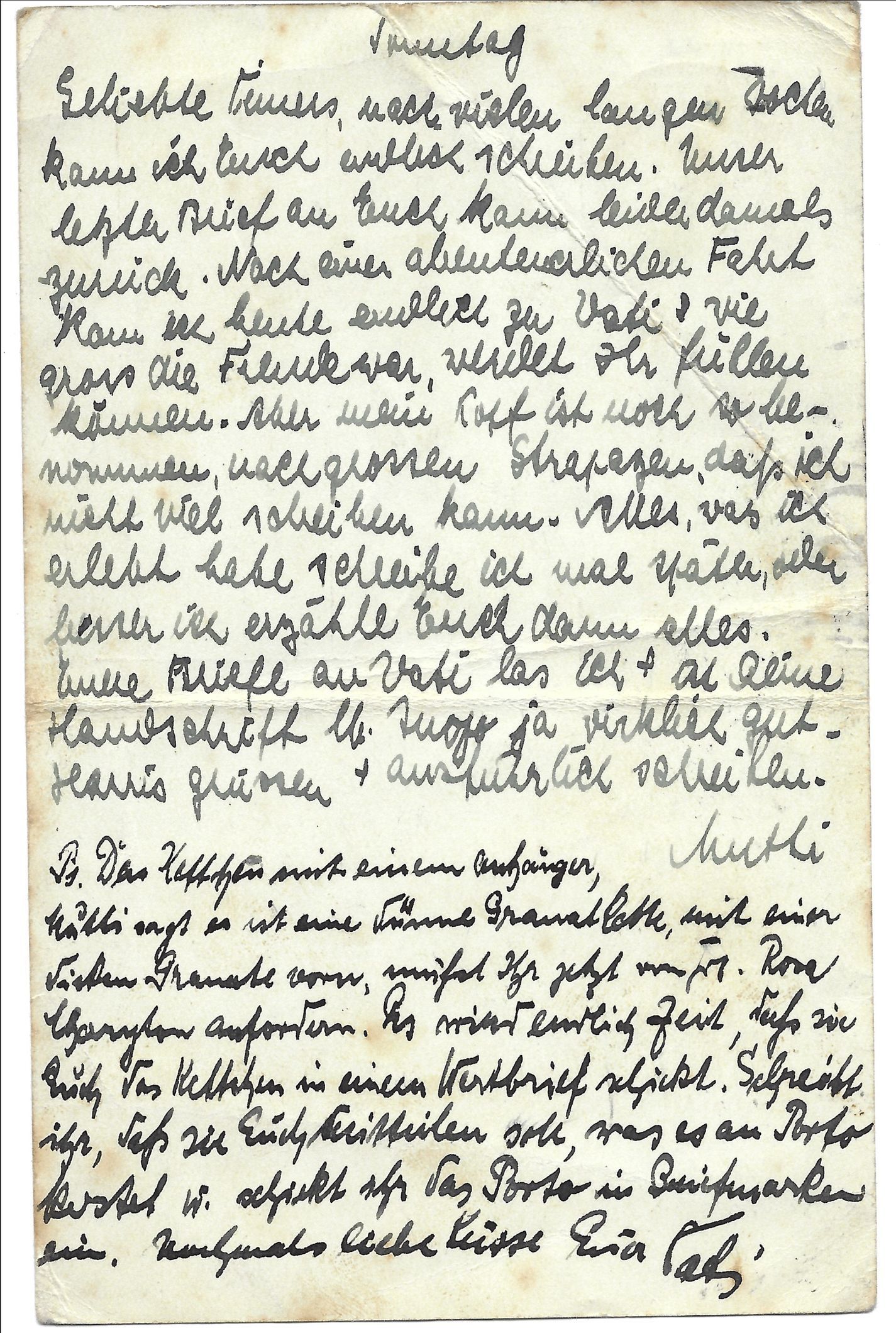

Throughout this time, their only family contact was through letters. At first, these letters were frequent and long, with the parents trying to bring up their children from afar, checking out their clothes, their school reports, giving advice about behaviour and education – and confident for a future where they would all soon live together again in America. In May 1939, they even agreed with their children that the girls would write on a Saturday so that this letter was received by their parents on the following Tuesday and an immediate reply could arrive in England by the end of the week, on the Sabbath.

This efficient plan could not survive war. When Henny and Hermann became refugees in France, they found themselves anxiously awaiting letters in a deteriorating postal system. France had become an enemy of Britain, so it was difficult to send or receive mail between the two countries. Henny and Hermann continued to write once a month to their daughters and waited anxiously for replies that never came. They suggested new routes for the post. These included writing through a mutual friend – a fellow Jewish teacher, Max Ruda, who lived in Zeurich, in neutral Switzerland. The International Red Cross helped with some postal arrangements, and there were suggestions about sending letters with a reply slip via organisations in Lisbon, but it was a rare occasion when a letter got through – and a time for celebration when a bundle of several very occasionally turned up all at the same time.

As Henny wrote,

'It was a great joy and surprise for us when finally a letter from you arrived, and we are even happier that you received the six letters from us! In any case, we have many worries but our greatest joy is when we receive good and frequent letters from you.'

In France, people increasingly recognised the presence of police terror, informers and collaborators in their communities. They shared less with each other in their conversations, and letters became comparatively bland. Henny and Hermann no longer mentioned the names of any of the people who were helping them. Everyone was beginning to wall themselves into a silence that they hoped would give better security.

By 1942, everyone was grateful for any letters because they showed that the people who mattered to them were still alive. These letters came ultimately to tell merely the often trivial details of their daily lives, and remembrances of happy times that they had once spent together. In the end, it mattered only that a letter confirmed that the correspondent was still alive, that they sent a message of reassurance that they still deeply loved the recipient, and the affirmation that they all continued to hope and pray for better times.

For Henny and Hermann's daughters, letters from their parents had been arriving increasingly infrequently and always delayed, and then they just never came at all.

(photo shows a postcard from Henny and Hermann to their daughters, October 1939)