Remembrance Day 1945 for German PoW

When an armistice was signed between the Allies and Germany on 11 November 1918, Herbert Sulzbach was an officer in the German army. It was a shattering experience for him to have to read out the terms of the armistice to the men in his command and return, dignified but defeated, to his country.

Between the wars, Sulzbach was on several occasions in London as a business-man on Remembrance Sundays when those who had died during that war were commemorated. He was much impressed with the grave and respectful attitudes that he observed in the people around him on those days and that remained with him as an inspiration.

During the Second World War, Herbert Sulzbach served in the British army. In January 1945, before war had ended, he was sent to work as an interpreter at a prisoner of war camp at Comrie, Perthshire. By Remembrance Sunday 1945, he was a captain in the British army working amongst 4,000 young German prisoners. He saw his role as not only interpreting German and British languages, but also interpreting British democracy to these young men.

Many of the prisoners had been fanatical Nazis. A few months before Sulzbach's arrival, a lynching mob had strung up and murdered a fellow-prisoner who had shown anti-Hitler sympathies. Since then Sulzbach had worked hard to change the attitudes and opinions of any prisoner who was ready to listen.

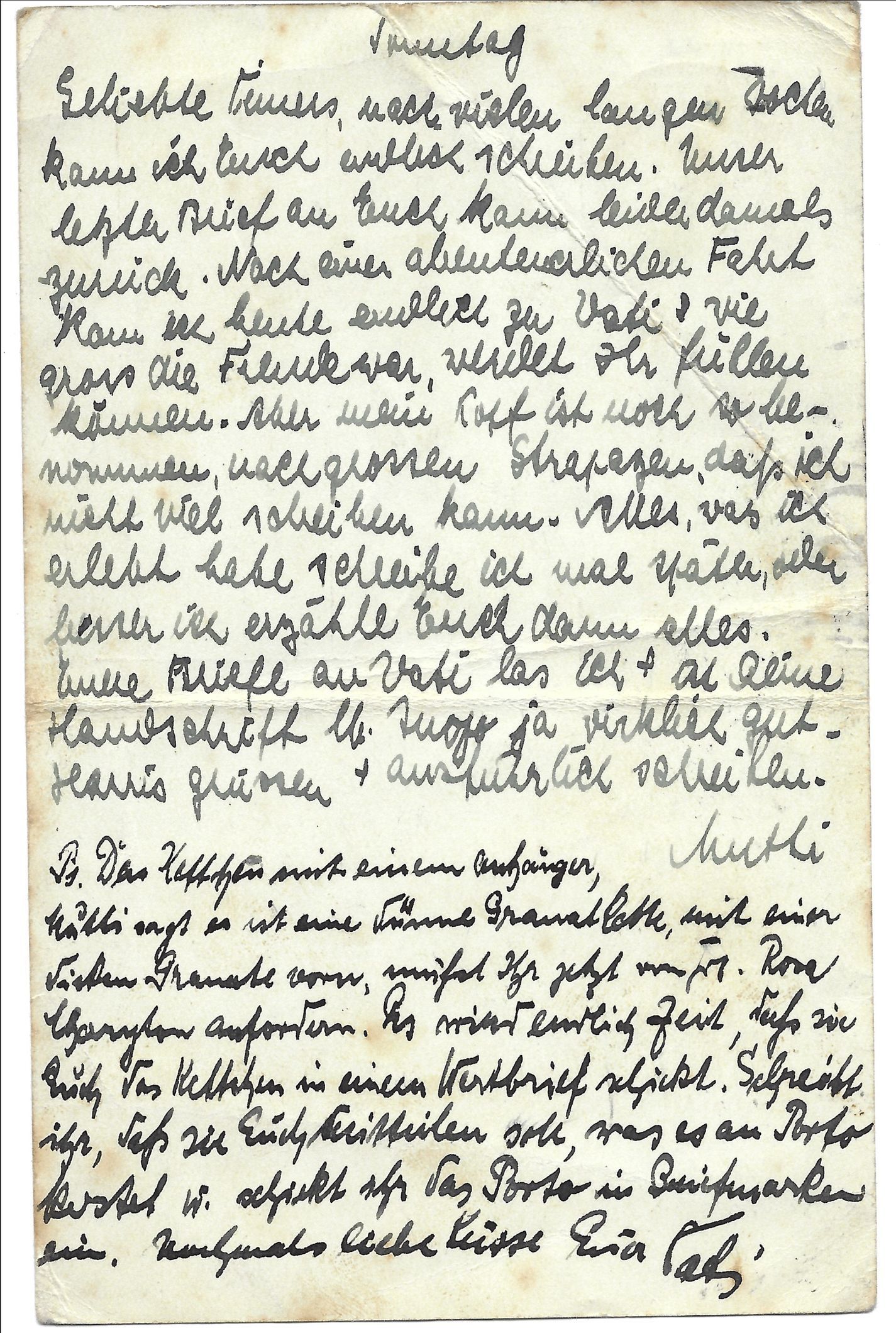

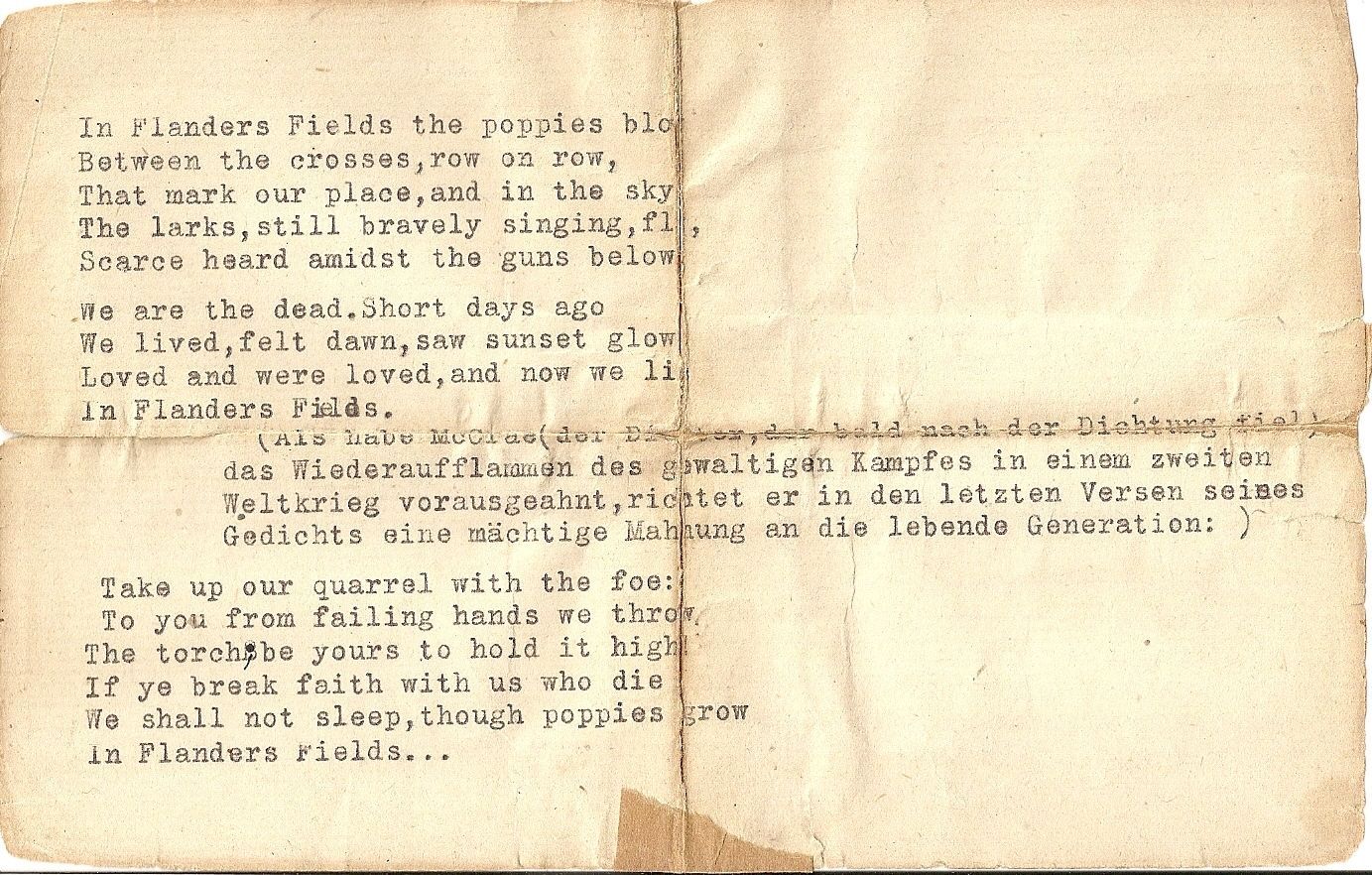

Shortly before 11 November 1945, he sent out a circular to all the prisoners. It explained that the focus of the Remembrance Day commemoration was on the dead of both World Wars. He also enclosed a copy of John McCrae’s poem, In Flanders Field, and suggested that the prisoners should only attend the ceremonies if they were prepared to take a vow. The vow that he wrote stated:

‘Never, never again shall such murder happen in future. It is the last time that we will allow ourselves to be lied to and betrayed. It is not true that we Germans are a superior race. We are all equal before Almighty God, whatever race or religion we belong to.

'At this moment we swear to return home as good Europeans and as long as we live to take an active part in the reconciliation of all people and the maintenance of eternal peace, according to the principle of the true, the beautiful, the good.'

Sulzbach added: 'Only if that is your own conviction, should you take part in these minutes of silence.’

Thousands of prisoners paraded, affirming the vow. Only a few remained in their huts, and Herbert Sulzbach was pleased and proud.

(the photo shows Sulzbach's battered copy of the poem that he sent to the prisoners)