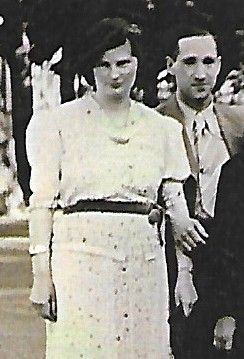

reconciliation after WW2

Yehudi Menuhin said of Herbert Sulzbach's work at Featherstone Park PoW camp that it 'healed and encouraged the human heart and spirit', and 'furthered and generated mutual respect and mutual trust'.

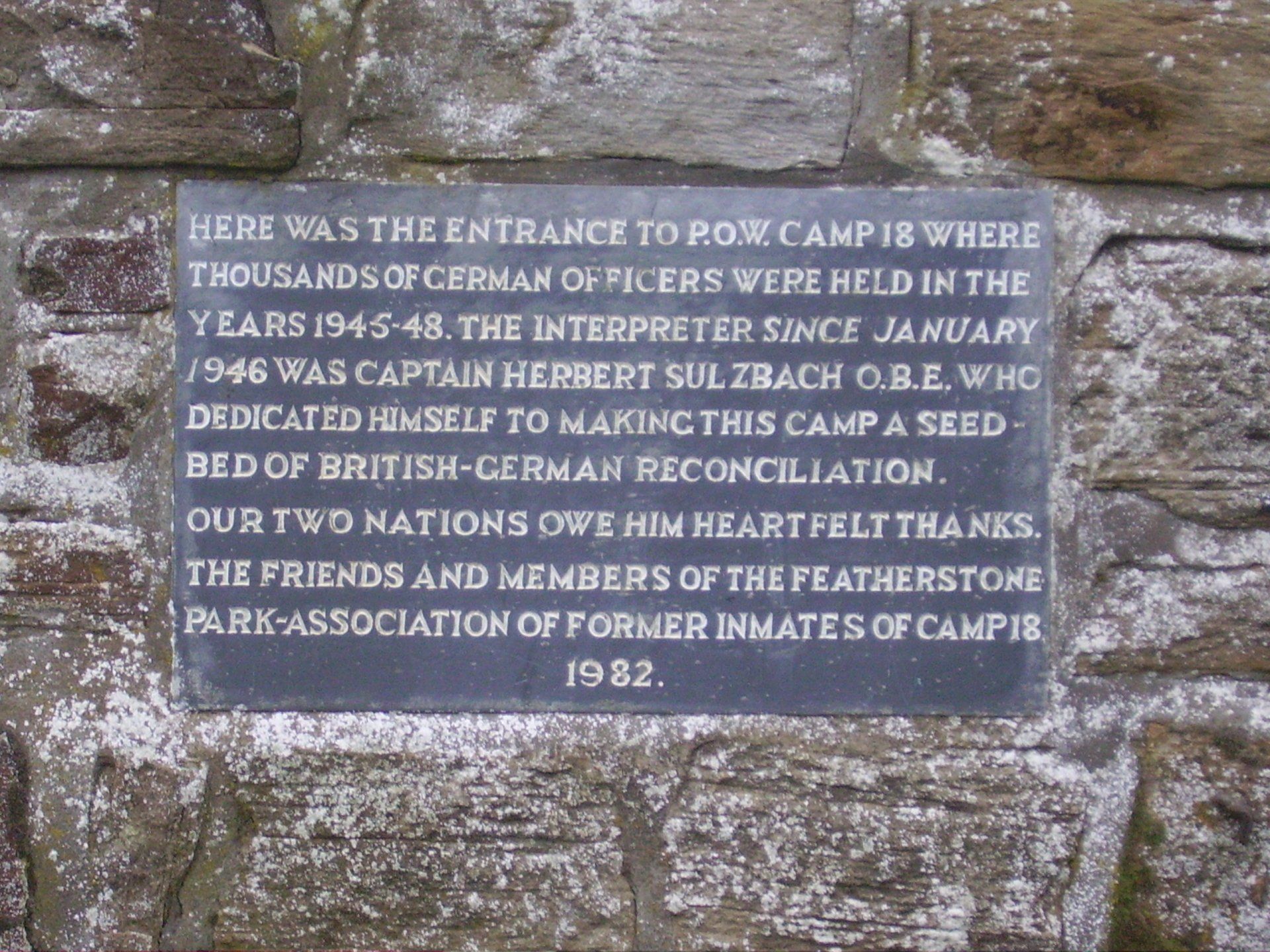

Yet Sulzbach was working in the immediate post-war period, amongst German officers, and he was himself a Jew. The violence, displacement and personal loss of the previous years were still vivid in people's memories. How was reconciliation to be possible?

His own explanation was that 'hatred leads to self-destruction. My ideal was Anglo-German friendship and reconciliation, based on a united Europe.' He immersed himself in as many one-to-one conversations as possible, with significant results.

Sulzbach had understanding of both the German and the British character, and also the necessary empathy to put himself in the German officers' place and see the world through their eyes. He helped them to face their own responsibility for the atrocities of the recent past and to understand the truth of the situation.

He knew that reconciliation would be a long-term process, and require not only their changed moral perception but also a commitment to justice and truth. This would need to include institutional transformation in the new Germany. Many of the PoW officers returned home to influential positions and demonstrated exactly that commitment to the country that they needed to rebuild.

A new German Consulate opened in London in 1951, and Sulzbach joined as a cultural officer. For the next thirty years he remained passionately involved in Anglo-German friendship and reconciliation. Partnerships and exchange programmes were arranged, town twinnings set up, and every opportunity taken to promote and deepen mutual understanding.

Reconciliation is an endeavour for the long term and Herbert Sulzbach was committed to it until the very end of his long life.