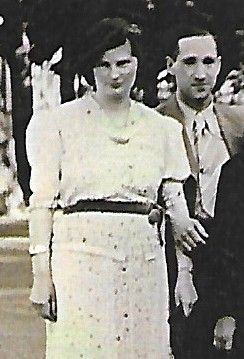

Henny and Hermann Hartog in Paris 1940

'Dear children, since Sunday evening Mutti [mummy] and I have been brought separately to these two camps. We have no idea what will happen next. Please write to this address and I will write to you. Write also if you get news from Mutti. Stay brave in life, and if the dear God wills, he will bring us together again.'

Hermann Hartog wrote this note on a postcard to his daughters in England in May 1940, after being taken from Brussels into an internment camp at Stade Buffalo in Paris. At this time of chaos and confusion, French officials used the large spaces of sports stadiums as places to intern suspect people arriving from Belgium and the Netherlands after the German invasion. These people included anti-Nazis and Jewish refugees fleeing Germany.

Stade Buffalo was a huge velodrome that could accommodate 30,000 spectators for different sporting fixtures. (It is now a housing complex). On his arrival from Brussels, Hermann was separated from Henny and taken there with thousands of other men.

Henny was taken to a different velodrome about three kilometres away from Hermann's. The women's holding centre was at the Vélodrome d'Hiver, close to the Eiffel Tower. This was an enormous glass-roofed stadium and as the women waited on the stone benches normally reserved for sports spectators they cringed nervously as German aircraft flew overhead – expecting any moment for the building to be bombed and for the roof to shatter in yet another 'Kristallnacht'. The weather was very warm that May and the stadium became very hot.

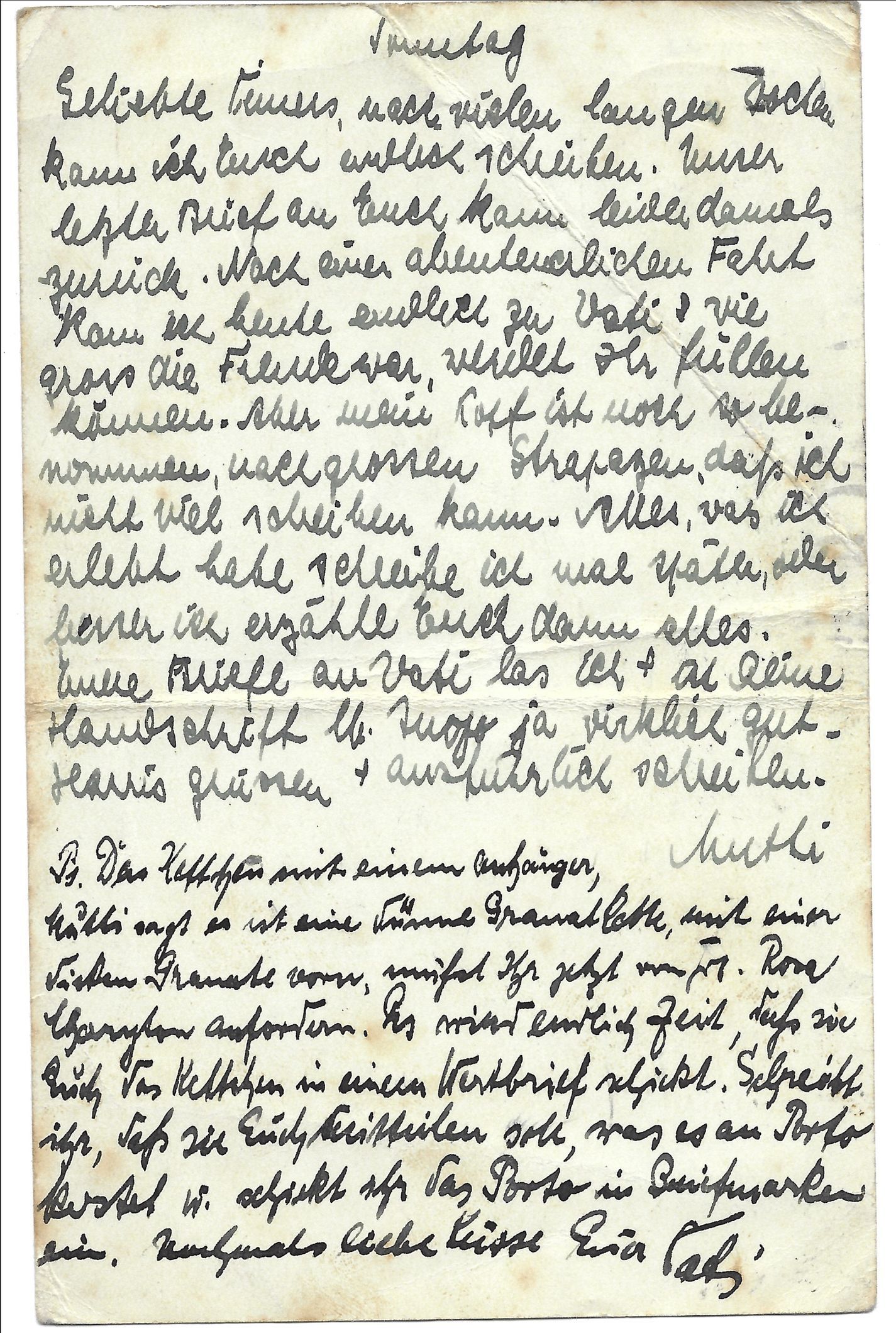

Neither Henny nor Hermann knew where the other was, nor what was going to happen to them. Their separate short letters to their daughters over these few days show - perhaps for the first time – a faltering in their optimism for the future. As Henny wrote to them,

'I am sure that you are very happy that your parents are alive. I think about you very often, my dear children, but I do not think that I can write very often. I kiss you a thousand times!'

A few days later, on 23 May 1940, Henny and Hermann were taken separately – probably in cattle carts on trains – to different internment camps further south in France. Hermann found himself at a camp in Bassens, not far from Bordeaux, and Henny was taken to Camp de Gurs, about 250kms away from Hermann.

(photo shows the site of Stade Buffalo today, now a housing complex)