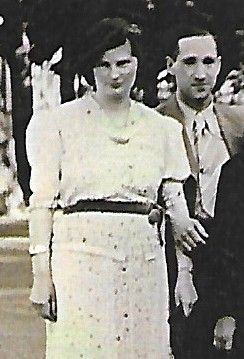

Final service at Neustadtgödens

Neustadtgödens is a small town in north-west Germany, about 20km south of Jever, where in the 1920s and 1930s Hermann Hartog worked as the Jewish teacher. He also had the care and concern of Jewish communities outside Jever and so regularly visited Neustadtgödens to teach the children there and also on occasions to take services at the synagogue. By the 1920s, the Jewish population had diminished to about 28 people (about five per cent of the town's population) and Hermann was visiting to teach just four children.

The Jewish community in Neustadtgödens struggled on for a few more years under an increasingly powerful Nazi presence in the area. In 1936, the synagogue was issued with an order to close by the local Nazi authorities, who alleged an unstable roof and disrepair. Although this was subsequently proved untrue, the community had by then become so reduced that there were insufficient members – only twelve - to maintain the building.

On 15 March 1936, a final 'celebratory' service was held at the synagogue. The rabbi of the province, Samuel Blum, attended and Jews came from far and wide for the occasion. The synagogue choir from Jever attended under the direction of Hermann Hartog and the soloist from Jever, Rudolf Gutentag, sang. Dr Blum gave a sermon and chose from Psalm 43 as his text:

''What are you grieving for, my soul?

And why are you so restless within me?”

Memories of the event have been passed down over the years, and it has been said that the singing rose the roof and that it was a magnificent and joyous occasion – albeit a farewell. The synagogue was packed and music and singing filled the building.

Two years later, the synagogue was sold to a non-Jewish carpenter from Wilhelmshaven. So, when the pogrom against the Jews took place in November 1938, the synagogue in Neustadtgödens was not burnt down – to have destroyed the property of an Aryan would have resulted in claims for damages. But the local Jewish men were still arrested on that night, and their money and valuables were confiscated before they were taken to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, along with other Jews from the area.

Today, the building that was once the Jewish synagogue still stands in Neustadtgödens and is cared for by curators from the Schloss Museum in Jever. It has been transformed into a powerful reminder of the Jewish heritage of the town and informs the visitor of its history.

(the photo shows the synagogue as it is today)