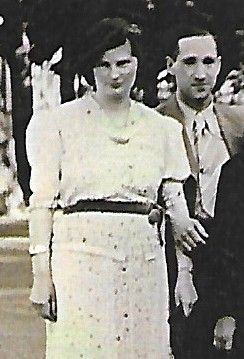

Henny and Hermann say goodbye in Spring 1939

Theirs was a forced emigration, and they planned carefully. However, circumstances changed all the while as they tried to make arrangements, and so plans were constantly having to be altered. It was only after the pogroms of November 1938 that Henny and Hermann Hartog had finally had to accept that they could no longer stay in Germany – but opportunities for emigrating were closing swiftly everywhere.

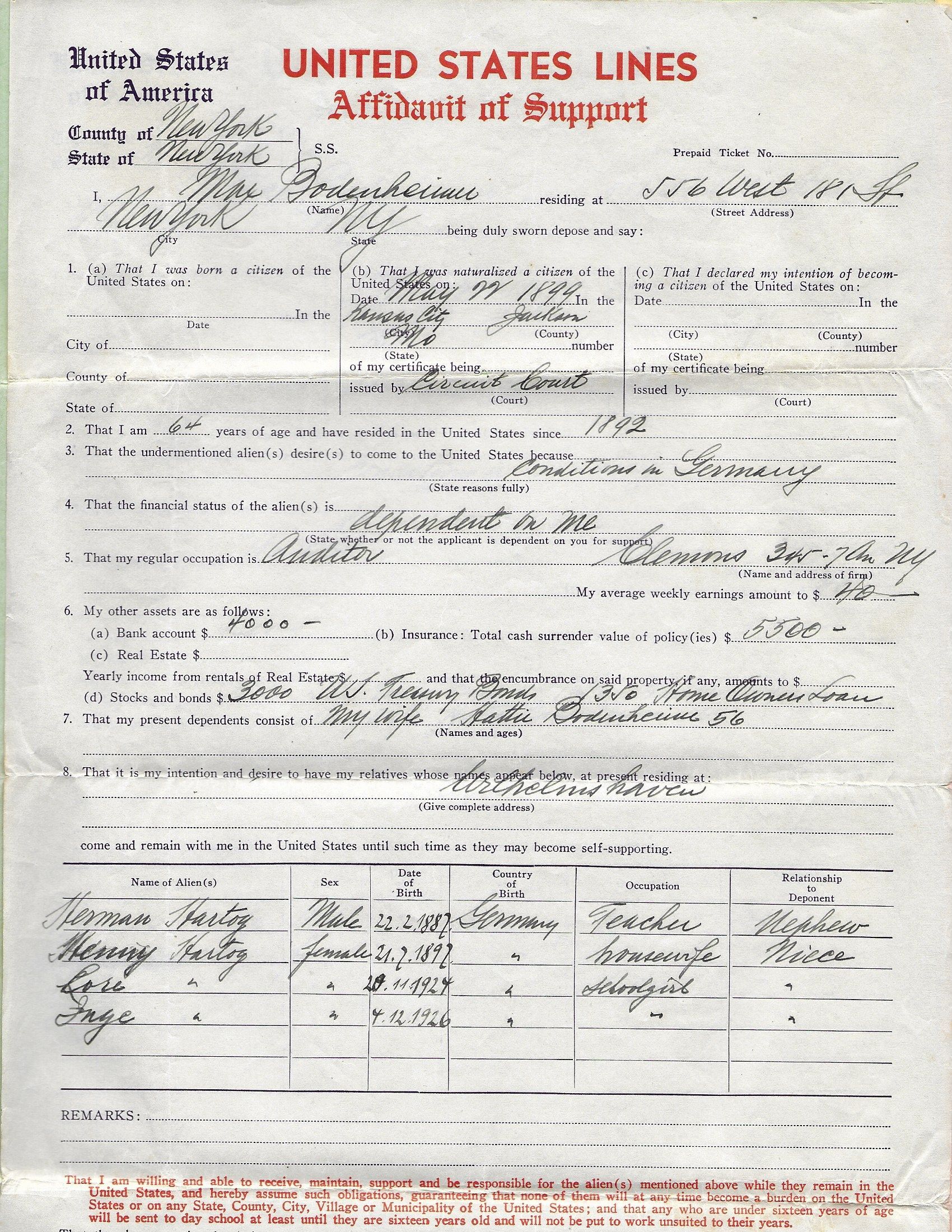

By early 1939, they were trying to travel to relatives in America – to be joined there later by their two daughters in England – but waiting lists were lengthening rapidly. Their plan changed to find a way to emigrate to England, but there were huge obstacles to entry.

Meanwhile, Henny arranged for many of their belongings to be taken in a container to the port in Bremen ready for shipping, but before long the costs of freight became so high, and money became so scarce, that they realised that this was probably not achievable. They left the 'Jew house' to which they had been allocated in Wilhelmshaven and went to live with Hermann's relatives in Aurich. Henny's father was already there; six adults in a not very large house.

In April 1938, Henny travelled to Frankfurt to say goodbye to her elderly relatives. She enjoyed the journey and the fine weather, and was pleased to see hills and forests again after the flat moorlands of the north of the country. The old people were thinner and frailer than she remembered them, and she worked hard to make life easier for them. She made a detour as she returned to Aurich in order to say goodbye to Hermann's sister who lived in Cologne.

In Frankfurt, she had also been preparing a place for her elderly father to live with his brother-in-law. Adolph Scheuer left Aurich for Frankfurt in May 1939, having made his home with Henny and Hermann for the previous nine years.

Friends and neighbours in Aurich were all leaving if they could, although many of the young people had already gone. The Jewish teacher, Max Moses, left for Hamburg and the USA, and Hermann took his place teaching the few children who remained.

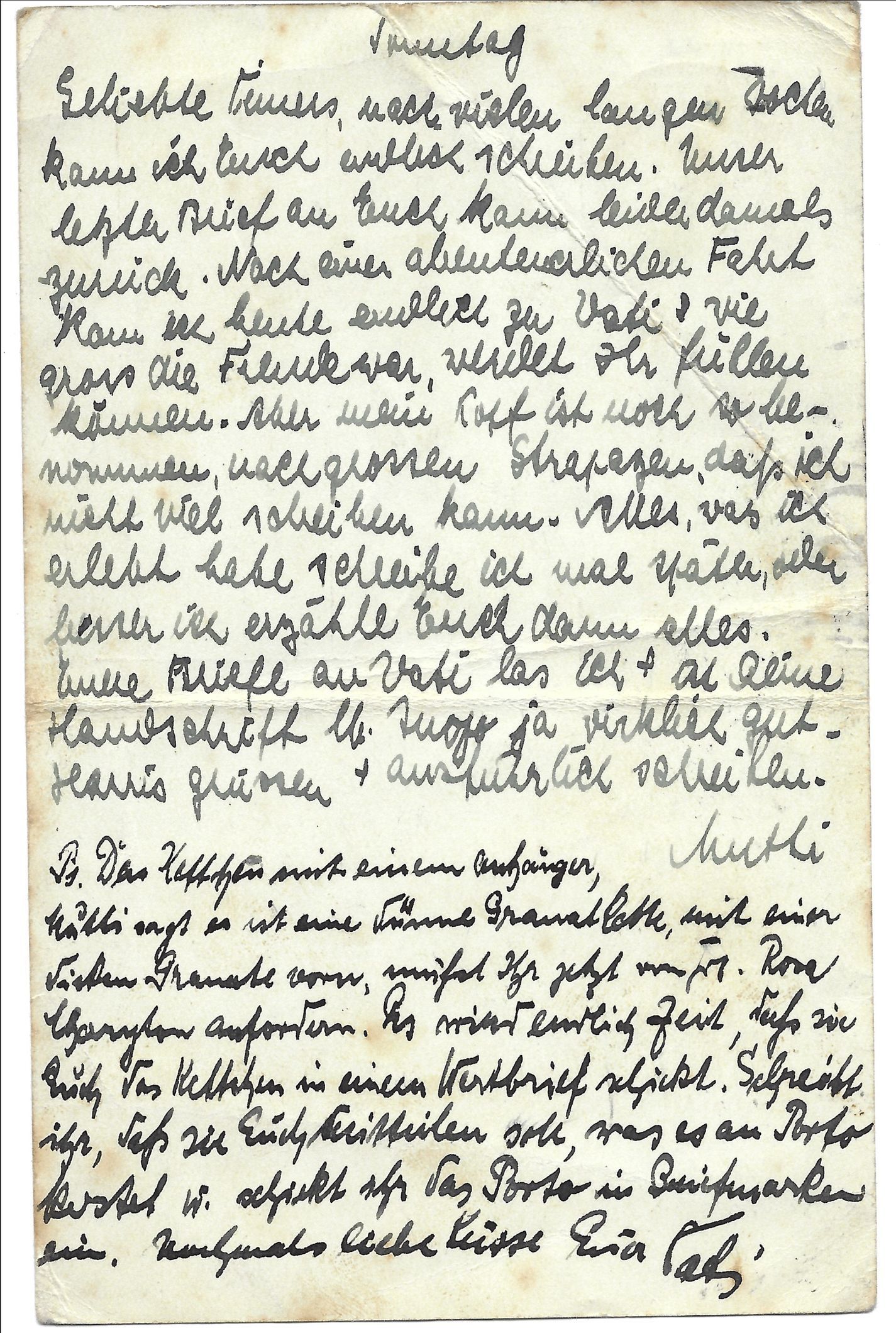

All plans were hurriedly shelved when war broke out in September 1939, and a few weeks later Hermann arrived in Brussels to find a place where Henny could join him. She managed to get there in November 1939. At that time, they had little idea that their farewells to relatives and friends had been final. They had become refugees.

(the photo shows Henny's father, Adolph Scheuer, in 1938)